about

Press

Road & Track

December 1999

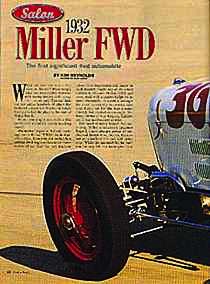

What do you see when you look at this car? Most people who are reasonable familiar with racing history will recognize it as an early Thirties’ Indy car, not unlike hundreds of others that blistered around the Brickyard before they padlocked the place at the start of World War II.

What, you might ask, makes this particular example worth reading about?

The answer begins with those markings on its flanks: “FWD.” As in four wheel drive. Moreover, the world’s first serious 4wd high-performance automobile of any kind, the very machine whose faint fingertips linger on such modern machinery as Porsche’s Carrera 4, Nissan’s Skyline GT-R and every Audi with a quattro badge on its stern. Personally, I’d count it amongst the most technically innovative cars ever built, yet for the wax-mustachioed, hat-cocked-at-an-angle Mr. Harry Miller of Los Angeles, California, it was just business as usual.

Not heard of Harry Miller? Not surprising. Miller is America’s forgotten Bugatti, a now-obscure genius of mechanical design who, like the Franco-Italian, visualized his cars with artist eyes. While the automobiles he built won the Indy 500 nine times (plus three more with his engines in other chassis), and accounted for 83 percent of the Brickyard’s fields between 1923 and 1928, these days his name would bring mostly blank stares from the thousands who click past the Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s turnstiles.

However, by 1931, Miller’s story had stopped being a succession of happy chapters. The Great Depression had put the racing world into cardiac arrest; his intricate, tightly would cars had suddenly become expensive, out-of-step relics of the Roaring Twenties, automotive jewels incongruent in the soup-line Thirties.

Actually, Miller seemed to sense all this coming in 1929, and while still on top, shrewdly sold his assets and (it was presumed) expertise to a group of overly optimistic investors (who named the soon-to-founder business Schofield-Miller). Then, in characteristic fashion, Harry simply ignored his responsibilities and spent his time traveling, enjoying his ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains (which was officially considered a zoo because it held so many animals) and his investigations into paranormal phenomena (a longtime interest). It took a thinning wallet to finally end the hiatus.

Reviving his old company, Miller plunged into a wild series of new projects, including an overhead cam head for Model A Ford blocks, and a replacement high-performance drivetrain for the Cord L29 (Miller’s front-drive patent had been used in the production version’s design). Then there was a series of elaborate racing-boat engines, including a 1113.5-cu.in. V-16 for Gar Wood, the internal dimensions of which would later resurface in the 4-cylinder “255” engine (this, in turn, being the blueprint for the epic Offenhauser engine that dominated American racing until the Seventies). And naturally, he turned to creating a new Indianapolis engine, this time a 230-cu.-in. straight-8.

But this time things weren't clicking. Miller was spending money like crazy on too many risky endeavors, and the cash just wasn’t flowing the way it did in the Twenties. Wages weren't being regularly paid. Ace machinist Fred Offenhauser began to put lies against the building's machinery in place of missing paychecks. And Miller started looking for ways to save his business with one all-conquering machine, a final throw of the dice. A car every racing tram would have to buy to stay competitive.

In the Twenties, Miller had first build conventional rear-drive cars, and then very successfully front-drive machines. Maybe the way to dominate Indy again would be to combine the two drive systems? Perhaps--but it would be an expensive proposition, impossible for Miller to finance alone.

After an Indy win in 1931 with one of the “230” straight-8 cars, Miller and friend Harry Hartz traveled to Clintonville, Wisconsin, to visit the FWD Company, longtime builders of commercial 4wd machines. Would they entertain underwriting a 4wd racing car? Not unimportantly, Miller was born in Wisconsin, and he and FWD Company's founder, Walter Olen, hit it off; the always persuasive Harry came away with a deal.

What actually happened (and much to the FWD Company's later consternation) was that Miller began to build two 4wd racers in Los Angeles. One, as per the agreement; the other, he hoped to sell (cheaper to build two cars at once, Miller figured).

Powering the “4wd cars” would be yet another entirely new engine, a 308-cu.-in. V-8 with dohc, drawn up by Miller's remarkable draftsman, Leo Goossen. The drivetrain foreshadowed what would become the 4WD automobile's ubiquitous architecture: From the transmission (a 3-speed), power would be transferred laterally to the car's passenger side via a gear-set, and then into a lockable differential from which drive shafts emanated, these connecting the engine's estimated 300 bhp to differentials at both ends of the car. Like the front-drive Millers, the front wheels were located by a De Dion tube, and all four wheels were sprung by pairs of quarter-elliptic leaf springs. Altogether it made for a handsome, purposeful (almost brutish) package, composed of beautiful detail design (by Goossen), exquisite workmanship (by Offenhauser) and a supreme quality of surface finish (a Miller hallmark). The FWD cars must have been a horrifying sight for the competition.

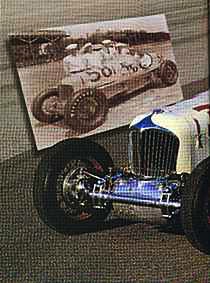

At the Speedway in 1932, one of the cars represented the FWD Company, the other (after much wrangling) was entered by Miller himself. The former machine (the one photographed for this story) was driven by Bob McDonough, who ran well but started far back in the pack owing to late qualifying, and soon dropped out with oiling problems. Meanwhile, after only three laps, Miller's own car, driven by Gus Schrader, stormed to 3rd place from 28th starting spot, but slid into the wall after its own oil coated the tires.

Bad omens, these. The V-8 was proving troublesome, exhibiting an unabashed appetite for main bearings. In 1933, the FWD Company's car qualified 2nd, but consumed its bearings and dropped out. For 1934, its engine was replaced by a Miller-design "255" (un-blown) 4-cylinder, and led the race for 60 laps, though it finished 9th due to lengthy pit stops. In 1935, the car dropped out while being driven by Mauri Rose, but in 1936 Rose managed to place an impressive 4th. A thrown rod in 1937 retired it (temporarily, as it turned out) from competition.

Meanwhile, Harry Miller's circling creditors were finally swooping in for the kill, at long last forcing bankruptcy. As a consequence, his FWD car was sold for peanuts to a Los Angeles business man who then sent it to Europe where it was entered in the 1934 Tripoli Grand Prix in the hands of Peter De Paolo. Perhaps because of De Paolo, Mussolini treated the American team kindly. Less gracious was the Italian competition: In the race, the Miller's lack of road-racing-appropriate brakes and chassis left it in 7th position, well aft of the winning Alfa Romeo of Achille Varzi (nevertheless, this represented the first showing of a 4wd car in a Grand Prix).

Later, De Paolo entered the car in a Grand Prix at Avus, Germany, where the Miller's V-8 exploded while again running 7th. The event was won by a streamlined Alfa Romeo Tipo B, but the rather more interesting aspect of the race was the reported story that the engine's disintegration occurs precisely before Adolf Hitler's viewing area. A nearby general evidently saw a fragment hurtle past the Führer's head (the Miller/Goossen/Offenhauser team was good--but not that good). The car was sent back to the States where the chassis was ultimately lost. However, the V-8 was repaired by famous Bugatti expert, the late Overton "Bunny" Phillips, who fitted it to a Type 35 chassis where it is today (in fact, recently the Bugatti-Miller was restored to spectacular condition).

And what of Harry Miller? After the bankruptcy, he struggled for years at a variety of creative but doomed projects (after the two 4wd cars, the steadying influence of Goossen and Offenhauser departed when the men left for greener pastures). Preston Tucker appeared and reappeared in Miller's later years, first in relation to a production road car based on the 4WD machine, later as an instigator of the pretty but not terribly successful Miller-Fords. There were more racing boat engines, airplane engines, and the incredible mid-engine (and 4wd) Gulf-Miller Indy cars. Eventually he wound up in Detroit suffering from diabetes and cancer, although it was a heart attack that killed him on May 3, 1943.

But for the remaining Miller FWD, that was not quite the end of the story. In 1947, in upstate New York, William Milliken, an expert in aeronautical dynamics (Bill worked on the B-17 and crewed on the B-29's first flight) heard about the Miller FWD that still sat in the FWD Company's showroom. Would they like to part with it for a while to gather insight into 4wd handling behavior? An agreement was reached, and Milliken raced the car at Pike's Peak (where the transfer case broke), at the second Watkins Glen Grand Prix, and at the Mt. Equinox Hill Climb, which Milliken won. (Partly due to his Miller experience, Milliken's curiosity in automotive performance has led him to become perhaps the world's authority on automotive vehicle dynamics.)

Bill (who is driving the car in our photos) remembers that at Pikes Peak, the neutral-handling Miller preferred a special driving technique: Carefully steer into the apex and then stand on the power as the car drifts sideways toward the outer edge of the road. He also discovered that on the Peak's dirt surface, the center differential had to be locked to give any handling predictability at all. Bill drove that car until 1953, when it was returned to the FWD Company, but during those five years, a lot was learned about 4wd performance, decades before it became fashionable in rallying.

Today the car is owned by Dean Butler of Cincinnati, Ohio, and is cared for by his brother, Don, and ace mechanic Jim Himmelsbach of Zakira's Garage. Interestingly, the Butlers are also caring for another legacy, an unfinished book by the late Griffith Borgeson titled The Last Great Miller: The Four Wheel Drive Indy Car. With Bill Milliken's help with the last chapter, Griff's final work is now complete, due to be published by SAE.

Epilogue

In Mark Dee's wonderful 1981 book, The Miller Dynasty, he mentioned that the building in which Harry Miller revived his business in 1933 (and where the 4wd cars were built) still stood at 6233 Gramercy Place, dead-center in Los Angeles. The building's facade is shown in a black-and-white photograph with Miller (wearing a white shot-sleeved shirt, necktie and hat) together with 23 of his employees (including Leo Goossen), all grouped for a company family photo, snapped 67 years ago.

Could the building still be there? Curious, I headed for one of L.A.'s oldest quarters, Making a right turn off Gage Avenue and going north onto Gramercy, the answer was there on the left: a low brick structure capped by a gently arching roof line, accented by bands of yellow brick.

The street was quiet. The building's quaint awnings were gone, and the multipane windows long since sealed over, converting the attractive storefront into an expressionless warehouse. Other than some minor graffiti, the structure evidenced scant signs of human life except for a For Sale sign glinting in the afternoon sun.

Standing in the street roughly where the photographer had taken the picture, I shook my head: we Americans are sorry caretakers of our history. In Europe, people wander the hidden corners of places like Molsheim and Maranello to sniff the history of Bugatti and Ferrari. But 6233 Gramercy, the last remaining structure where America's greatest racing cars were created, is desolate, waiting for the wrecking ball.

To the building's right was another brick structure, occupied by a charitable organization called World Vision, and there I met Phyllis Freeman, an extremely pleasant woman who explained that World Vision distributes donated clothes, food and learning materials to the needy (indeed, a shipment was being prepared for Turkey's earthquake victims).

I showed her the photo of the building next door and she blanched, having no idea of its history. After a quick tour, Phyllis led me to a different part of the structure, where she stopped, smiled and suddenly announced that we were now within the interior of the Miller quarters (it turns out that the two buildings are actually connected). Dim and crowded with cardboard boxes atop pallets, this realm where Miller, Goossen and Offenhauser dreamed and toiled and polished aluminum might be a silent, forgotten place, but it's not useless.

1932 Miller FWD

The first significant 4wd automobile

by Kim Reynolds

photos by John Lamm