about

Chris Leydon: Once Retired

Like all living people, I have a past, present, and a future. This website is devoted to all three. The past is represented by a photographic portfolio of my achievements as creator of Leydon Restorations, Ltd; the present and future, by a project page where I describe current challenges and mischief which dominate my attention. My desire is to share the passions that have driven me, acknowledge the contributions of others who have supported me, and to highlight the adventure as I navigate forward.

The Early Years:

Albuquerque, New Mexico, may not be the most propitious place to start one’s earthly career for there are certainly more favorable spots to develop a fanaticism with the motorcar. However, one of the first sounds welcoming my birth came from my father's just reassembled 1927 supercharged Mercedes. To be sure, my whines were less music to his ears than the crank driven centrifugal blower, but soon his enthusiasm for me, and I for his interests in vintage race cars, would form a lasting bond that would propel me into my vocation.

I was born into a Navy family where every two years initiated a new stop and a new start in a new town and each "tour of duty" included additional voiturettes and vintage cyclecars with which to climax the fatigue of starting and stopping. Moving inventories included packing carburetors with curtains, shocks with socks, water pumps with swimming trunks, etc. My mother, fearing this somewhat chronic abnormality was reaching new heights (or depths) when my father succeeded in smuggling a B29 bomber sight under his bed next to the Isotta Fraschini headlights, laid down “Mother’s Laws” redefining territorial imperatives and ground rules of governance: God and family on the Sabbath and the like.

In most cultures, familial and sometimes national bonds are strengthened by specific “rites of passage” which elevate boys to manhood, girls to womanhood, and philanthropists to sainthood. In my family, this rite deviated somewhat from the norm: each of the three boys received cardboard boxes and orange crates filled with what was reputed to be a French racing voiturette. The passage part of the rite was to piece the somewhat complicated puzzle of parts back together making as many mistakes as possible thereby deriving the greatest possible learning experience. For my father, the two hundred dollar investment provided unending possibilities of imaginative birthday and Christmas presents with which to enhance our education. This emersion in an eccentric and loving family—where patience, compassion, and cooperation were in abundance—provided the foundation for my life that was to follow.

By the time I had learned to speed-tune my bicycle, transportation dominated my life. Fond memories include pedaling to our neighboring town to spend mornings with the venerable George Green. George, an old German machinist and, at one time, the local 1903–1910 Oldsmobile dealer, was a man of considerable mechanical skill. He ran his entire shop on an ancient stationary engine (“Otto”) which he had converted to diesel. One single-filament lamp bulb hung from the shop’s ceiling illuminating a fabulous circuit of line shafts, flat belts, and a comprehensive den of machinery. For me, it was a place of wonder and excitement. He’d peer over his Franklin spectacles as I unlashed from my bicycle the component that was providing me a challenge, and then with patience, survey what remedies were possible. This immersion in the early twentieth century seemed normal to me at the time. It is only now, in its recollection, do I recognize how precious it was.

In my teens, we moved to Washington DC where the Smithsonian Museum of American History and the National Gallery of Art became my second homes. After school, I roamed their corridors, absorbing cross-sections of the Knight sleeve-valve engine and the evolution of mechanical governors in the one and the fantasies of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Hieronymus Bosch, in the latter. It was here where I was to be schooled in the beauty of both form and function and appreciate their marriage in things mechanical. This continued through high school where I competed and won a National Merit Scholarship that sent me packing for a stint in Point Barrow, Alaska, doing studies on carbon dioxide and ozone. Little did I appreciate that the data was being sent to and studied by a future vice president and his college advisor.

I suppose it wasn't especially earth-shattering news to my father when I announced my desire to go to engineering school. I had become greatly absorbed in the pure sciences and in the nature of materials. Off I went for a four year training on how to out-think Mother Nature and remedy the products of “Murphy's Laws.” To reduce my financial dependence on my parents, I formed a company to broker British sports cars in the US. I traveled to Great Britain during the summers, purchased cars, and imported them for sale during the school year. Additionally, I worked nights and weekends for a former technical vice president of Rolls Royce restoring Silver Ghosts and facilitating his efforts in engineering studies on vibration fracture. School was a great luxury, sort of an institutionalized fortress which cradled me in its arms and provided security enough to dream of conquering the unimagined. I would even wander past mathematical logic into the science of human relations where even to this day I have never felt comfortable.

After four years, the bubble burst with honors upon graduation and I quickly learned that people don’t eat diplomas. Within a month, I was given a GS rating and was madly studying everything available on inertial guidance. Working for the Navy as an electrical engineer, I helped develop a data entry system for jets on aircraft carriers (CAINS, carrier aircraft inertial navigation system). In time, I experienced burn out, paused briefly for a five thousand mile bicycle trip through western Europe to get the wanderlust out of me, became the director of a vintage air circus to purge some remaining romanticism, and then launched a new business rebuilding vintage cars to prove to my future father-in-law that I could support his daughter. My ambition was to become the best and it took forty years to prove that goal both foolish and elusive. However, the journey proved exciting and encompassed architecture, construction, business management, and every discipline of applied science known to man. What a ride!

Leydon Restorations, Ltd:

Vintage restoration is not unlike childbirth and during my long engagement in the craft, which included agony and ecstasy, joy and pain, it continued to redirect my life’s vicissitudes toward higher plateaus of knowledge, patience and often humility.

Because the automobile is a product of the marriage between art and science, my learning opportunities were endless. I delighted in being absorbed by every industrial trade and material composition represented in automotive construction. Machine tool cutting theory, spectrographic analysis, alloy material science, cell structure in hides, computer aided design, casting technology and the like, all dominated my every day interest. Each new job became an archeological “dig” and a new inquiry into the process of salvaging history with a keen eye for authenticity. Like many of my customers, I felt nurtured by this shop and its artisans.

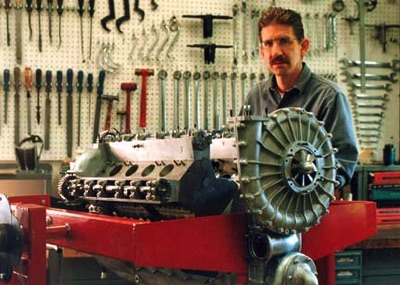

What is not often consciously perceived is that the product of a restoration shop is really craftsmanship. To sell craftsmanship, you must develop within yourself and the people you employ, a commitment toward excellence. To produce an excellent product, enthusiasm, knowledge, and patience must be coupled with skill and long experience. Resumes reading “machinist on prewar Alfa Romeo and Bugatti engines with a quarter century of experience seeks position” are not the common drugstore variety. Thus, the restoration shop that I developed became a vertically integrated business with an huge investment in machinery and tooling that no ordinary profit motive business would stomach, and this was coupled with a commitment to elevating the skills of all those who worked there. In time, it proved its capacity to execute every engine machine operation, support these efforts with a complete tool and die facility, and able to dyno test engines with greater ease and precision than any competitor.

This commitment toward excellence often jeopardized financial solvency but like childbirth, the pains of its labor were most always eclipsed by an appreciation and joy in the product.

What Next:

An effective life skill is to learn to dream. Like Don Quixote, I need a windmill or two to advance a new charge into adulthood and my dream takes form in the disposition of thirty-five acres smack-dab in the middle of the state of Colorado. It is here where Rita and I, with the help of our sons, will design and build a new (green) home. It will be a place of refuge, a place of music and of textiles, of literature and mechanical inquiry. A place of peace and happiness.

Playing the nyckelharpa and dancing in many different Swedish dialects.

A random collection of accolades and press clippings from a long life in the automotive restoration business.

My philosophy as it relates to life, the universe and everything.

The shop I created in my past life was spectacular. Let me show you around.

.4

.2 About

About