about

by Dennis Adler

It was a balled up mass of steel. Once proud. Now shattered. The lean, single-seat body was rumpled along its length from hitting the wall in one turn, and the great Maserati grille cleanly divided by an infield tree, where the car had finally come to rest. Driver Bud Sennett was unhurt. The year was 1951, the 35th running of the Indianapolis 500 Mile Race, and the last appearance at Indy for the Maserati 8CTF.

What, you might ask, was a 1938 race car doing at Indianapolis in 1951? The answer was simple: It was doing what it had done since 1939—giving the American cars a run for their money.

The 3.0-liter 8CTF was a car that might never have been were it not for Adolfo Orsi's purchase of Maserati from the fratelli in 1937. Brothers Ernesto, Ettore and Bindo remained "privileged" employees, moving race car development from the original factory in Pontevecchio, Bologna, to Modena. There they were given a limited budget by Orsi to design and build two new 3.0-liter Grand Prix cars for 1938 to challenge the Mercedes-Benz W 154 and mighty 12-cylinder Auto Union D-Types.

The Maserati brothers actually had done quite well in Grand Prix racing before Orsi's involvement with the Scuderia, producing a 2.5-liter car in 1930 which won five major races. An even more powerful version developed in 1933 was victorious in the French and Belgium Grand Prix. However, by 1935 it was clear that the Tedeschi were going to dominate Grand Prix racing, and lacking the finances to compete with the German automotive empire, the fratelli switched to the smaller 1.5-liter voiturette class. For the next few years the Maseratis produced some very competitive four- and six-cylinder twin ohc single-seaters, but even that effort finally strained the small firm's racing budget to the breaking point.

All Orsi had wanted from the Maseratis was their spark plug business to fold into his own SAS conglomerate, which, among other things, also manufactured spark plugs. With Orsi's money, Ernesto, Ettore and Bindo could take their profits while continuing to build racing cars at Orsi's expense. The arrangement was ideal for the Maserati brothers.

The resultant Tipo 8CTF, though based on the 1937 4CM, used an enlarged version of the voiturette class box section welded chassis, torsion bar independent front suspension, and quarter-elliptically spring rigid rear axle.

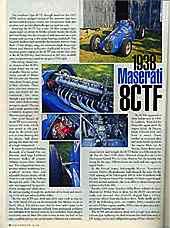

Powering the 8CTF was a new 3.0-liter straight eight engine made up of two 4CM-like cylinder blocks—the block and head being testa fisa (one-piece) and mounted on a new bottom end carrying a five plain-bearing crankshaft. The Maserati brothers had essentially doubled the formula from their 1.5-liter design, using the voiturette's single Roots-type blower and Memini carburetor duplicated in pairs. The resulting power output of the 8CTF was exactly twice that of the 4CM-350 bhp (later increased to 365 bhp) at 6000 rpm, and promising a speed in top gear of 156 mph.

One strong characteristic element of the 8CTF's engine design was the use of smaller Memini carburetors instead of Weber DC45s, with one Memini twin-choke for each group of four cylinders. There were also two compressors, one driven by the crankshaft, the other through a gear in the cam drive tower, both turning at engine speed. The car use a single ignition with a Scintilla magneto and Maserati spark plugs.

One novel feature of the 8CTF was a cast magnesium oil tank, which also served as the platform fro the driver's seat and as cross bracing for the chassis. Talk about getting the most use out of a single component

To meet the continual braking demands of a Grand Prix car, Maserati used large Lockheed hydraulic brakes all around, 400mm drums front, 360mm rear. The independent front suspension utilized wishbones, longitudinal torsion bars and adjustable friction shocks, which could be seen clearly by looking through the grille. The live rear axle was supported by quarter-elliptic springs and radius arms, the springs passing through the underside of the body and attaching to the axle just inboard of the brakes.

The first two 8CTF cars, 3030 and 3031, were ready in time for the 1938 Tripoli GP, run on the ferociously fast Mellaha circuit in North Africa. The drivers were Achille Varzi and Count Carlo Felice Trossi. Both Maseratis suffered from mechanical problems and withdrew from the race early on, but not before Trossi charged dauntlessly past all three Mercedes entries to take the lead on lap eight, a gallant gesture that served notice: Maserati was a contender.

The 8CTFs appeared in three Italian races in 1938. At Leghorn, Trossi led the Mercedes again until the engine failed. At Pescara, Luigi Villoresi took over from a weary Trossi, worked up to second place and made the fastest lap before the engine blew up. AT Monza, Trossi drove more conservatively and brought the 8CTF home to a fifth overall finish. For the final 1938 effort, Maserati shipped a car to the Donington Grand Prix in Great Britain, but the gearing was wrong for the race, Villoresi drove too hard, and once again the engine broke.

In the United States, Indianapolis Motor Speedway owner Eddie Rickenbacker had changed the rules for the 1938 running of the Indianapolis 500 in order to conform with the new European Grand Prix formula: 3.0 liters supercharged, 4.5 with normal aspiration, this in an effort to attract foreign auto makers to the Indy 500.

For the 1938 event, American Mike Boyle ordered the latest Maserati for Wilber Shaw to drive, but the 8CTF cars were not ready, and instead the fratelli shipped him a 1.5-liter voiturette, which Shaw declined to drive. Boyle finally got his 8CTF the following year, car number 3032, complete with an extra 3.0-liter engine, number 3033, a box of spare parts and a selection of Maserati spark plugs.

The 8CTF arrived stateside fitted with a single large-diameter exhaust pipe replacing the dual exhausts that had been used in GP racing, one for each independent group of four cylinders. The car was thoroughly gone over by Boyle's master mechanic Cotton Henning before being handed over to Shaw.

Having become well aware of the 8CTF's mechanical frailties under pressure, Henning adjusted the blowers to produce a maximum output from the straight eight of 350 bhp, shaving 15 bhp off the factory's specifications and probably saving the engine. Henning also fitted the 19-in. wire wheels with Firestone tires in place of the Pirellis that has been used in Europe

Shaw was immediately taken with the car and found his already estimable skills enhanced by the Maserati's responsive handling. Making full use of the 8CTF's four-speed gearbox, independent front suspension and clean, low-drag bodywork, Shaw quickly seized the lead, winning the 1939 race with a two-minute margin and giving Maserati a decisive and important victory. It was the first time a European car had won at Indianapolis since Peugeot in 1919! To prove that the Maserati's victory was no flash in the pan, Shaw entered the car the following year and won again with nearly a full lap leeway!

In addition to Shaw's "Boyle Special," in 1940 cars numbered 3030 and 3031 were campaigned at Indianapolis by the French team of Lucy O'Reilly Schell. The color scheme for the Schell Maseratis was French Blue with crossed French and American flags painted across the hoods. From the start, things went badly for the Schell team, which was only able to qualify one car composed of teammate René Le Bégue's 8CTF body and frame, number 3030, fitted with the engine and transmission from René Dreyfus' car number 3031. Earlier, Dreyfus had blown up the engine in Le Bégue's car during the test run. Sharing the remaining Maserati, Le Bégue and Dreyfus finished a dismal 10th to Wilbur Shaw's rousing second Indianapolis 500 victory with his 8CTF.

In 1941, Shaw seemed headed for a hat trick with only 120 miles to go and leading by almost a lap, when tire failure denied him his third consecutive victory. It was not a total loss for Maserati, however. Duke Nalon, driving one of the French 8CTFs, which had remained stateside due to the war, finished 15th.

Postwar Racing

After four years of neglect, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was in grave disrepair, the elements having mercilessly ravaged the grandstands and track by the summer of 1945. Owner Eddie Rickenbacker lacked both the finances and the desire to put the Brickyard back into shape. What could have been the end of America's greatest race track was nipped in the bud by Wilbur Shaw, who arranged for the sale of the speedway to an Indiana businessman named Tony Hulman, Jr. The rest, as they say, is history.

Shaw, who became president of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, had more than a passing fancy for the two Maserati 8CTF race cars that returned for the first postwar race in 1946. The car pictured, number 3030, was entered that year by Frank Brisko as the Elgin Piston Special, and driven by Emil Andres. Wearing number 18 and a new paint scheme of maroon and white with gold lettering, the eight-year-old Maserati managed on impressive fourth-place finish, behind Shaw's old Boyle Special and given over to Ted Horn.

Losing ground to adversaries who had at last built more advanced cars, number 3030 Maserati was not entered in the 31st Indy 500. However Horn, still driving Shaw's old 8CTF, finished third once again.

In 1948, Harry McQuinn, driving for Frank Lynch Motors, put number 3030 on the starting grid but lasted only one lap before one of the superchargers blew up. Horn again finessed Shaw's car to the finish line, this time taking fourth. Number 3032 raced one more time in 1949, with Lee Willard driving, but retired on the 55th lap with a broken transmission. After 1950, the car was replainted in the colors characteristic of Shaw's time and placed in the Motor Speedway Museum.

The number 3030 car, now owned by R.A. Cott and driven by Harry Banks, failed to qualify in 1949, and another attempt to field the Maserati failed in 1950 with Danny Kladis driving. Finally, in 1951, Bud Sennett managed to put the now 13-year-old Maserati in the race for owner Joe Brazda. It was to be the car's last appearance. The aged 8CTF lost its footing, slid hard into the south wall and spun off into the infield where it rapped headlong into a tree. Which is where we began.

The crumpled Maserati was towed back to the pit area and later examined by Sennett and Brazda, who determined that the car was a write-off. For all intents, that was the end of 8CTF number 3030.

Years later, repairs were attempted but never successfully completed. The one time it was started, the engine promptly put a rod through the block. Race cars, however, are a lot like weeds: Unless you completely destroy them, they have a habit of coming back. When collector Bob Rubin acquired the car some years ago, he knew its significance as one of the rarest Maserati race cars in the world. And, like the proverbial weed, it would come back.

Rubin chose the Maserati and Bugatti race car specialists at Leydon Restorations to restore the battered 8CTF, a project that Leydon tackled with all their resources, searching through historical files, photographs and Maserati history to pin down the exact specifications of the car. Leydon's conclusion was that it could be restored in one of two different configurations, in French Blue with the crossed French and American flags as it had been at Indy in 1940 or in the maroon and white with gold lettering, celebrating its fourth-place finish at Indy in 1946. Rubin decided of the original color scheme used by the Lucy O'Reilly Schell team in 1940. Completely reconstructed by Leydon, the car once again bears the name of driver René Le Bégue.

The second Schell car, number 3031, went through a 12-year restoration by John Rogers for noted collector Joel Finn. The Wilber Shaw car, number 3032, is still on exhibit at the Indianapolis Speedway Museum.

European Car

December, 1995

1938 Maserati 8CTF

The Conquest of Indianapolis

Press